Designing with an emphasis on empathy

Industrial designer Peter Cansfield layers a people-focused perspective onto technical expertise when developing new seating products

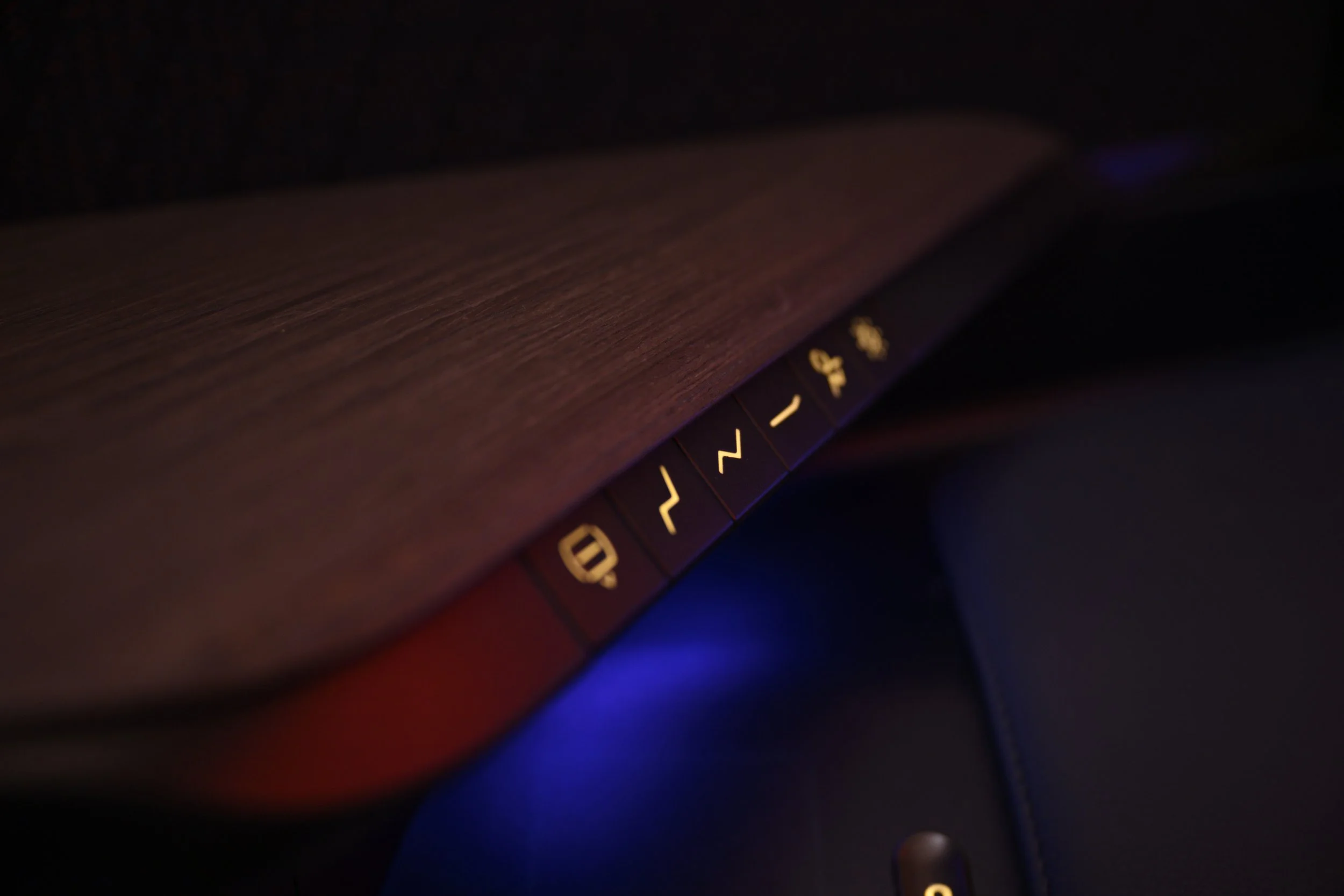

"Some people don't like to touch metal buttons. Who'd have thought, right?"

Peter Cansfield pauses mid-sentence, the weight of this seemingly simple discovery settling in. After 30 years designing luxury car seats in Detroit and two years crafting seats at Collins Aerospace, this veteran industrial designer has learned that the devil truly is in the details. And those details can make or break a passenger's eight-hour journey at 35,000 feet.

The uncomfortable truth about comfort

In an industry where airlines routinely receive feedback about comfort, Cansfield faces a professional paradox.

"When I read the feedback from what airlines get, where they talk about seats being uncomfortable, that doesn't sit well with me, being a seat designer," he admits. But after decades in the business, he's learned that comfort isn't just about cushions and legroom; it's about solving problems most passengers never consciously notice.

"Comfort is designed by the absence of discomfort," Cansfield explains, articulating a philosophy that drives everything from the tactile feedback of buttons to the smooth deployment of tray tables. It's a science that encompasses shin clearance, haptic textures, noise levels, and even the psychological comfort of knowing everything is within reach.

Cansfield’s philosophy on comfort includes seating elements like the tactile feedback of buttons to the smooth deployment of tray tables.

Beneath the surface: what really constitutes comfort

For Cansfield, comfort breaks down into measurable, designable components. Seating surfaces and foam density represent pure science that his team can master and deliver consistently. Ergonomics encompasses everything from tables positioned within natural reach to surfaces remaining within sight lines, ensuring perfect tactile feedback at every touchpoint. The sensory experience includes seemingly minor details like the sound of a deploying table, the texture of fabrics against skin, and the satisfying feel of switches responding to touch. Even accessibility transforms from abstract requirement to concrete design imperative when passengers say "I can't get my foot through this gap."

"There are so many different aspects of comfort, which we can go into," he notes. "It's a deep, deep subject and it hits every part of your experience inside of the seat, inside of the suite."

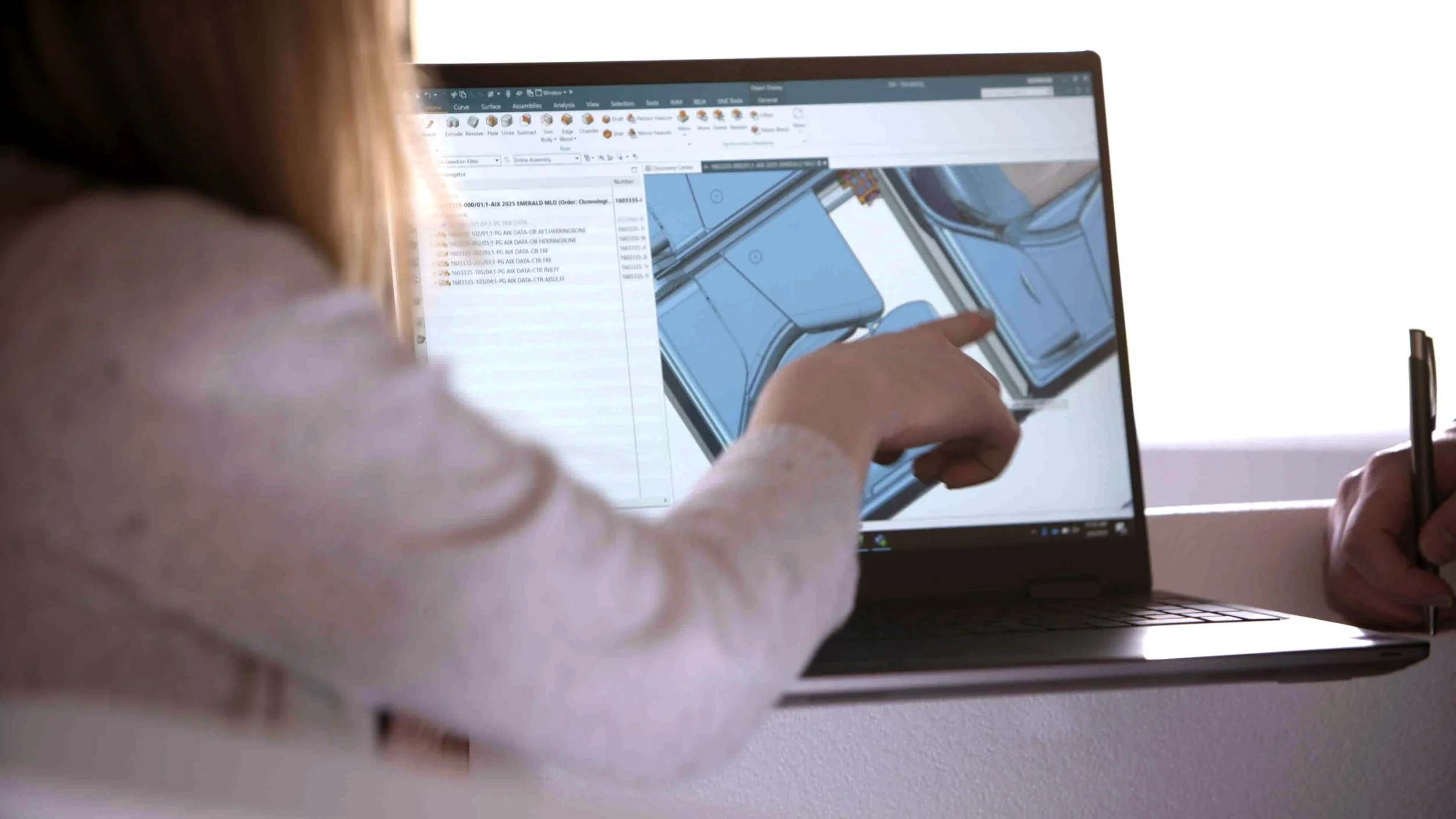

Design engineer Michael Boyd and senior technical fellow Glenn Johnson discuss the details of a new business class seat as represented by a foam mockup during a development workshop.

Designing for everyone

What sets Cansfield apart isn't just his technical expertise; it's his ability to see through passengers' eyes.

And passenger profiles are changing rapidly. Premium cabins are no longer just for the suited business traveler. Today's business class includes multi-generational families traveling together, Boomer grandparents with expendable income and grandchildren, first-time flyers from diverse backgrounds, and passengers with varying physical abilities and sensory needs.

"Not everyone is coming from a middle-class home in America. People could be on the plane for the very first time in their lives. What kind of experience are we giving them?"

Having a clear understanding of the passenger perspective comes into particular focus as it relates to designing for accessibility. When designing new concepts, Cansfield thinks about his father, who suffered a stroke and was left partially paralyzed. "I'm looking at these seats now through his eyes. What would his experience be like?"

This perspective has been especially valuable in recent accessibility workshops, where real passengers with diverse needs test seats in development. The goal isn't just compliance – it's discovering "those unmet needs, those little nuggets which we might have missed because we've all designed seats for the past 30 years with a certain amount of knowledge."

Design defined by compromise

Cansfield's role requires navigating complex relationships between customer needs, engineering and manufacturing.

"This is a side-by-side collaboration from day one," he emphasizes. "You've got to have a lot of faith in the engineering team you're working with, and they've got to have a lot of faith in you," Cansfield says.

The ultimate challenge lies in maintaining design integrity while meeting practical constraints. When airlines present concepts developed by outside agencies, Cansfield's team becomes the bridge between vision and reality.

"Design is a compromise. You've got to find the right compromise for the airline, for Collins, and the human experience on board."

Shaping future flight experiences

With global airline passenger growth predicted to double by 2053, the stakes for getting seat design right have never been higher. Cansfield's approach of combining deep technical knowledge with genuine empathy for diverse passenger needs offers a roadmap for an industry grappling with rapid change.

"We want to connect with people. We don't want to design just a latch, or a series of components that come together as a seat. We've got people to design for and we have to design with them in mind."

His message is clear: the science of comfort is real, measurable, and achievable. But it requires moving beyond generic feedback to understand the specific, human experiences that define passenger satisfaction.

"Better products are what we have to deliver to the marketplace, better products are what we have to deliver to the airlines, and better products, which we can make, is what we have to deliver to Collins. So, all of this plays into design."

In an industry where passenger experience directly impacts airline reputation and profitability, Cansfield's human-centered approach to design isn't just good engineering – it's good business. The question isn't whether airlines can afford to invest in this level of design thinking. The question is whether they can afford not to.

Seeing is believing

Visualization designer Fernando Rentas blends

art and technology to create realistic renderings

of future cabin experiences. >>

Minimizing downtime while maximizing quality

Manufacturing engineer Kevin Egbert leads a team of MRO professionals focused on repairing and returning galley insert equipment into service with both speed and quality. >>

Bridging aviation’s toughest gap

Certification chief Srinivasarao Boddepalli ensures galley inserts meet the meticulous standards set by both customers and the FAA. >>